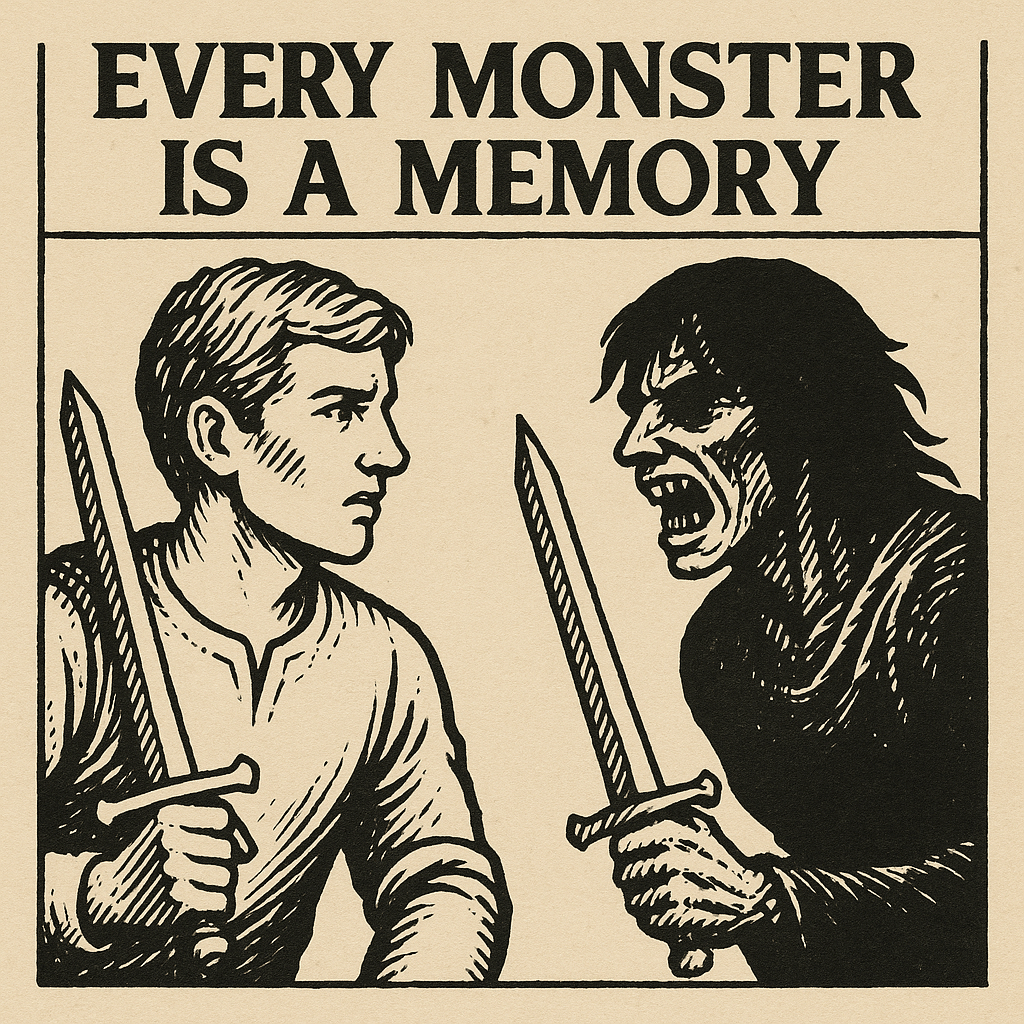

There’s a saying that fantasy worlds are mirrors, reflections of the storyteller’s mind, fractured into myth and shadow. In The Labyrinth of Time’s Edge, I’ve taken that idea one step further: the monsters that haunt you are not strangers. They are memories. Every creature you encounter, every NPC that lingers in the halls, is tied to an echo of the self. They are pieces of us we’ve forgotten, rejected, or buried, and when they rise again in the game, they do so with teeth and claws. They are the distorted fragments of the human experience made manifest, waiting in the dark.

Echoes and Fragments

When I design a monster for the Labyrinth, I don’t ask: What does this beast look like? Instead, I ask: What does it remember? A wandering husk might carry the weight of grief that was never spoken aloud. A faceless wraith could embody the fear of being unseen, unheard, or forgotten. Even a grotesque, flesh-bound creature clawing through the corridors might simply be rage, dressed in a form we can finally run from. These are not enemies placed in your path for the sake of combat alone. They are storytellers in their own right. Each one whispers a truth you may not want to hear.

Fear Made Flesh

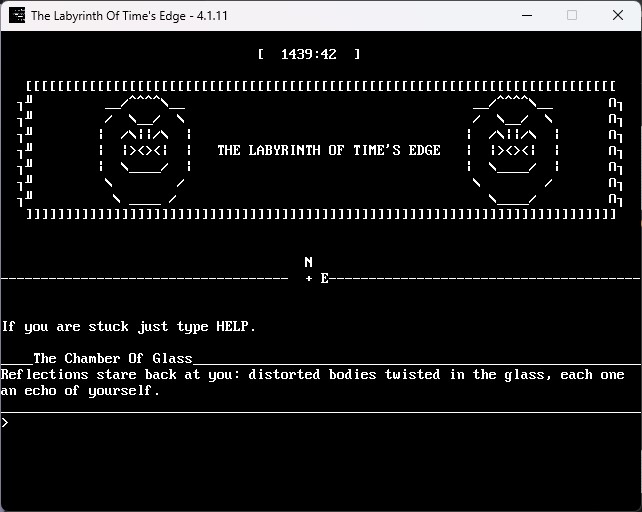

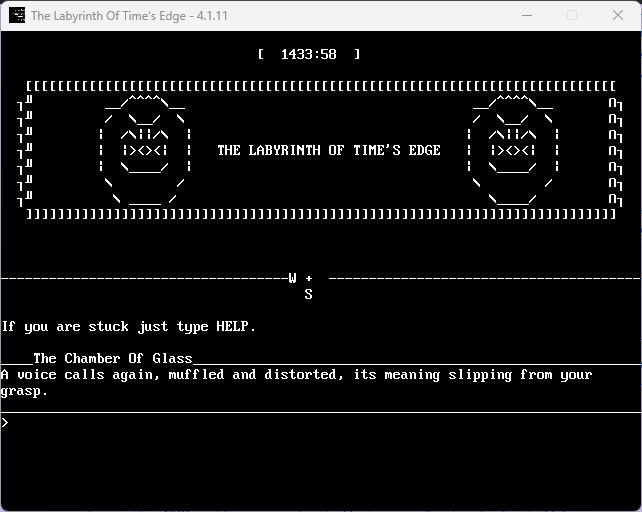

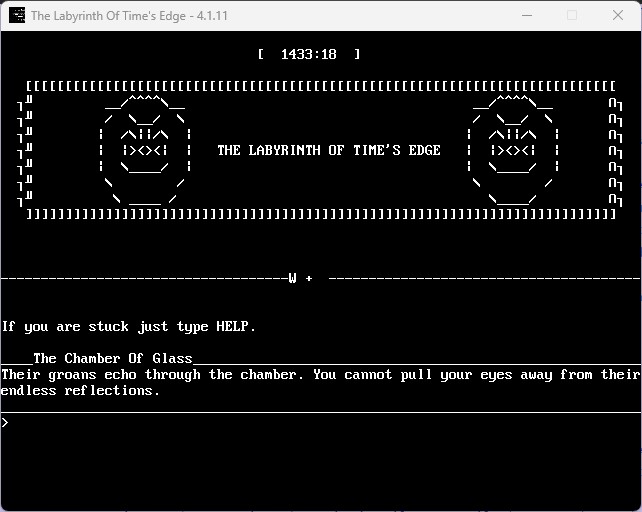

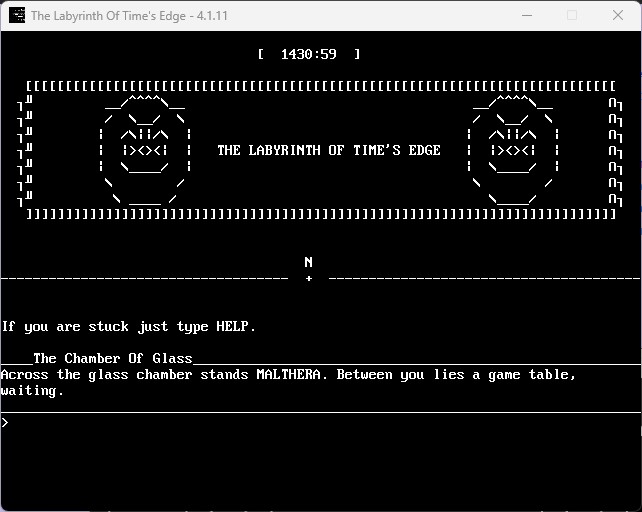

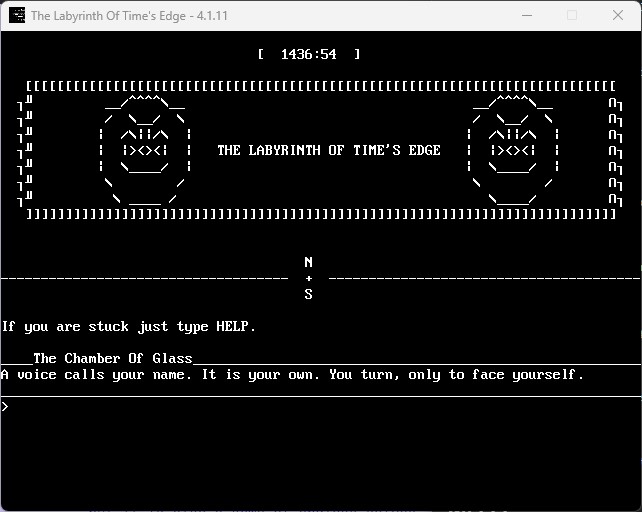

The Chamber of Glass is where this philosophy becomes clearest. Within those mirrored halls, you don’t fight nameless horrors from the void. You fight yourself. Reflections of your own body distort in the glass, twisting into figures that barely resemble you enough to be familiar, but warped enough to be terrifying. Then, at last, a darker double of you emerges, armed and laughing with the madness of recognition. It’s not simply a monster. It’s a memory of who you could have been, or perhaps who you still are, hidden behind the veneer of control. The encounter forces the player to consider: are you battling an intruder, or are you staring down the truths you’d rather leave unspoken?

NPCs as Living Memories

Even the NPCs, the ones who talk to you instead of striking, are shaped by this same philosophy. An old man in a cave isn’t just a guide. He might be the embodiment of weariness, a memory of days wasted, the shadow of “what if” that haunts us as we age. A priestess offering sanctuary may, in fact, be a reflection of longing, that part of the self still searching for peace in a hostile world. A witch who guards the ending is more than a villain, she is the boundary between the life we know and the unknown that waits beyond it. In this way, dialogue isn’t just flavor. It’s a confession. The NPCs are fragments of thought, given flesh and voice.

Monsters Within Us

Why take this approach? Because true horror doesn’t come from elsewhere. It doesn’t descend on us from the stars or crawl up from some distant underworld. The real terror is always inside us, our regrets, our broken promises, the memories that sit in silence until they are dragged, screaming, into the light. The Labyrinth is a game of endless rooms, yes, but it is also a game of endless selves. Each encounter pulls on a thread of identity, each monster an aspect of the player reflected in monstrous form. By walking the halls, you’re not just mapping a fictional dungeon, you’re mapping the human condition, one echo at a time.

Conclusion: The Doppelgänger Stares Back

“Every monster is a memory.” That is the design philosophy at the heart of The Labyrinth of Time’s Edge. The Chamber of Glass doppelgänger sequence is not just a set piece. It is a thesis: the labyrinth is not haunted by strangers, but by you. By your echoes, your failures, your possibilities. And perhaps that is why players return, room after room, even knowing the game may never end. Because in the shadows, in the broken reflections, they see themselves, and to face oneself is the greatest horror, and the greatest story, of all.

Leave a comment